|

|

PAPA People Assisting Parents Association © 2007 |

| Home |

Purposes & Services |

FAQ |

Archives & Links |

e Donation & Survey |

Contact Us |

|

Members Only |

MCFD Tactics |

Forum & Testimonies |

Parent Support |

Kid's Zone |

On-Line Services |

|

|

|

Hover your mouse to pause the slide show and to view photo description.

|

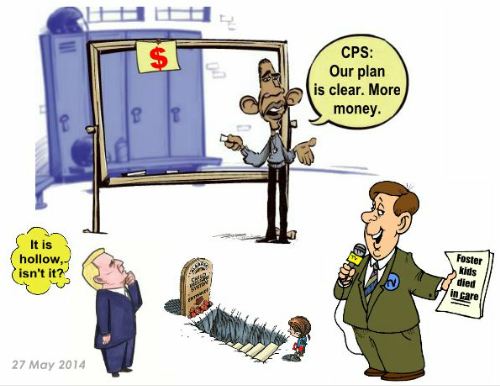

One-Month Old Manitoba Foster Baby Matias de Antonia Died In Care

After the media uncovered unreported death of Albertan foster children in November 2013, another scandal hit the child protection industry in March 2014. A one-Month old foster child died in care in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Unlike most provinces in Canada, law in Manitoba permits publication of the names of foster children who have died in care, if the information comes from family. This means that the family could go public without first having to apply to court to lift the publication ban.

The victim is baby Matias de Antonia born on 24 February 2014. He was seized by Manitoba's Child and Family Services (CFS) at birth for a concern that the ability of the infant’s mother Maria Herriera to care for him. The exact reason of removal is unknown to the family. The child died on 27 March 2014, 32 days after removal while in the care of CFS. Police say they investigated the death and found no basis to lay charges.

|

|

The Matias’ family is from Colombia. Their first language is Spanish. They immigrated to Canada in 2008, presumably to pursue a safer and better future in a so-called free and democratic country. Carlos Burgos, uncle of the deceased infant, said his 20-year-old sister Maria Herriera has been in Canada for six years and is a permanent resident. The grieving family said that they were not given much information on how the baby died, other than from a lack of oxygen to the brain.

The NDP government’s Family Services Minister, Kerri Irvin-Ross and members of the opposition Progressive Conservative party met with the family to discuss how to move forward with an investigation. The Minister made a commitment that there will be weekly contact with the family so they know what steps have been taken and what direction CFS is heading. Promise of weekly contact bears resemblance to the ruse used by the Malaysian government after Flight MH370 went missing in March 2014. It serves to placate anger of the relatives of the passengers until they lose steam in pursuing an answer for the missing plane.

At the point of writing, there is little information available to the public surrounding the cause of death and who should be held responsible.

The following are noteworthy in this case:

- Most Canadians think that child protection workers always have good reasons supported by good evidence before they remove children. Contrary to this popular belief, child protection service (CPS) may remove children without giving solid reasons in many cases. Often, a vague allegation unsupported by evidence, such as a child protection concern that parents lack ability to care for their children or less intrusive means are inadequate to protect children, is given to justify child removal. Another example is Jamie Sullivan of Edmonton whose 4-month old infant Delonna Sullivan was seized without giving a reason and the infant died after 6 days in an Albertan foster home. We have come across many parents who sought assistance from us facing similar situation. To our dismay, laws silently condones arbitrary child removals. We are not aware that those who abuse child removal power are held responsible in any court of law.

- Subsequent police investigation on foster children death often yields no result. Few CPS workers, foster parents and other service providers in the child protection industry get charged for criminal negligence. Very little information surrounding death of removed children is given under the pretext of protecting the privacy of the children and their family. The media customarily moves on to other news after airing some sketchy information. Public attention and interest soon fade. CPS gets away with murder. Another young life destroyed by the very agency that is supposed to protect young children.

- Parents are often left in the dark when their loved ones in care die, get sick or suffer an accident. Parental rights are deprived to protect service providers in the child protection industry from being sued and to mitigate the chance of getting unwanted publicity. Parents are compelled to go through a tedious bureaucratic process that often get them nowhere.

- Many politicians tend to protect the status quo for their own political benefits. Most politicians fail to see that they are sitting on a time bomb and could potentially become collateral damage when they have to pay a political price for the oppressive laws they have allowed to remain in effect. Their involvement and lip service often offer little real assistance to the grieving families after their loved ones fall prey.

-

Visible minorities and immigrants whose first language is not English are prominent targets scrutinized by CPS. In particular, Aboriginal children (which constituted 86% of the foster children population in Manitoba as of as of 31 March 2008, see source of data below) are high value targets as provincial child protection agencies receive federal funding on a per head basis. The Matias’ family bears remarkable resemblance with Aboriginals. Child protection workers may have mistaken Baby Matias de Antonia as a high value target.

Almost all immigrants have the common objective of pursuing a safer future for their children when they came to Canada. They will not get this as long as the government has absolute power to remove their children at will. Such power can be used to target any individual or groups of people for reasons other than child protection. The now-renounced residential schools, primarily established for cultural assimilation purpose, speak to this effect. State-sponsored child removal seriously jeopardizes our safety, freedom and liberty. It is a disgrace to humanity.

|

|

Lessons Learned From This Case

- As we have said before in other cases, a new death of foster child in care is not the first and will not be the last. The only solution to end this fiasco is to change child protection law to restore accountability and to prevent racketeering.

- Under the advice of some lawyers who may offer pro bono service to the grieving family, it is likely that the mother will file a lawsuit against the province. Prior to hearing, the Province may offer a handsome settlement with a non-disclosure obligation of any settlement details on this case to prevent drawing further unwanted public attention. Taxpayers always bear the financial burden of legal costs and possibly a huge court-awarded damages.

- In their infinite wisdom, most judges allege that foster homes are known safe places. They err on the side of caution and make custody order in favor of child protection agency. This case adds to the mountain of evidence refuting this irresponsible and unfounded assumption.

- Most critics of CPS believe that flaws resulting in death of foster children are insufficient funding, inadequate training of social workers and case overloads. Failing Our Children by Margo Goodhand published on 12 June 2009 supports the foregoing. They fail to see the oppressive and inhumane nature of state-sponsored child removal. Under the pretext of child protection, the industry is controlled by financially motivated service providers who remove children for job security and business opportunities. In all child protection hearings and mediation, parents and their supporters are the only parties who go there without getting paid. Too much power and money have been given to the wrong hands.

-

If you think that this is an isolated incident, the following deaths in foster care may change your view:

- "Edmonton mother Jamie Sullivan went public after her infant Delonna Sullivan died in care";

- "a 3-year old foster kid by Lily Choy, a foster mum in Edmonton in 2007."

These are just the tip of an iceberg. Of course, there are many foster child deaths around the world where governments have the absolute power to remove children from their families.

|

|

Source: Figure 1 on Page 8 of "BC Children in Care: Improving Data and Outcomes Reporting" by Ian McKinnon, BC Children and Youth Review (April 2006)

Provincial governing parties in 2006 were added by our editors.

Abbreviations: Progressive Conservative (PC), Liberal (Lib), New Democratic Party (NDP) |

The child protection industry in Manitoba

Aside from some minor differences, the child protection industry operates in similar legal, cultural and demographic settings with the rest of Canada.

Children under and up to age 18 are "protected" under the provincial statute Child and Family Services Act. This Act obliges everyone to report to the Department of Child and Family Services if there is reason to believe that a child is in need of protection. Reports of suspected child abuse can be made anomalously (ie. informants do not have to disclose their names). If informants choose to identify themselves, they are not legally responsible for information provided in good faith. Their name remains confidential except where required by the court and are protected from harassment for giving the information.

Like in most child removal regimes, there is no requirement of mandatory registration of CFS social workers with any professional governing bodies.

As mentioned at the beginning of this page, Manitoba law permits publication of the names of foster children who have died in care, if the information comes from family. Please read "Different Provincial Law on Publication Ban and Percentage of Population with Children Removed" to compare publication ban in each province.

According to the report "BC Children in Care: Improving Data and Outcomes Reporting" by Ian McKinnon, BC Children and Youth Review published in April 2006 (hereinafter known as the Report), Manitoba had the highest ratio of foster children in the provincial age group population of 0 to 19 (hereinafter known as the ratio) among all Canadian provinces (see the bar chart reproduced on the left). The Report indicated that the four Western provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba) had the highest ratio of children in care and higher Aboriginal populations in Canada. It drew no conclusion on the correlation between these two factors. Manitoba also exhibited a very high percentage of Aboriginal foster children (86% as of 31 March 2008 see below).

The Report alleged that Alberta has high quality reporting on data of child welfare (second paragraph on page 9). It does not further elaborate on the definition of quality on reporting. The aforesaid conclusion of the Report written in 2006 is clearly refuted by the findings the Edmonton Journal and the Calgary Herald in 2013 that the Alberta government has dramatically under-reported the number of death of child in care over the past decade. 145 foster children have died since 1999, nearly triple the 56 deaths revealed in government annual reports over the same period. The under-reporting of such embarrassing data is clearly to protect the child protection industry and not to draw public attention. How can deceitful and inaccurate reporting of the number of deaths of foster children be considered high quality?

In 2006 (the year in which the Report was written), four provinces with the highest children in care ratio were governed by parties across the political spectrum. This suggests that political orientation has little bearing on the ratio of children in care.

Child Abuse Registry

Some child removal regimes have child abuse registry to keep record of perceived child abusers. Manitoba has established a provincial Child Abuse Registry. In addition to guilty plea and court disposition of child protection matters, the opinion of the child and family service agency's Child Abuse Committee that a person has abused a child is sufficient to list a person as a child abuser on the Registry. Employers and other party with the person's written consent may apply for access to determine if a person is listed on the Registry. Other than an expensive, time consuming and complicated judicial review application in the Supreme courts, we are unsure whether there is other layman-friendly venue a person could use to rectify wrong bureaucratic opinion from the Child Abuse Committee.

Unlike criminal records in the Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC) where addition, removal and usage of CPIC data are governed by law [for example the Criminal Records Act (R.S., 1985, c. C-47)], record entries in Manitoba's child abuse registry are at the discretion of members in the Child Abuse Committee. Opinions from the Committee could be subjective, arbitrary, biased and could be made without a fair hearing. Since legal rights in the Canadian Charter only applies to criminal trials, parent's right to be tried fairly within a reasonable time and the presumption of innocence is being circumvented by the legal design that all child protection matters are civil in nature. Having a record in the child abuse registry is derogatory and may have a serious adverse effect on a person's ability to seek employment, emigration, adoption or a political career.

The Gary and Melissa Gates case in Texas aired by CBS 42 Investigates News on 10 July 2008 sheds light on how child abuse registry could be unjustly used against parents perceived as uncooperative and how bureaucrats could use it as a means to publish parents. Child abuse record could open another oppressive arena that may take wrongfully accused parents years and huge legal expenses to have their names removed from the registry.

Murder of the 5-year old Phoenix Sinclair by her parents on 11 June 2005

|

|

|

Hover your mouse to pause the slide show and to view photo description.

|

From time to time, child protection regimes are troubled by scandals and CPS-created atrocities. Our "Cases" page contains a number of embarrassing cases from various jurisdictions attesting the foregoing. Like the death of Sherry Charlie of British Columbia in 2002, the child protection industry in Manitoba attracted public scrutiny after the 5-year old Aboriginal Phoenix Sinclair was murdered in 2005.

Phoenix Victoria Hope Sinclair was born to Samantha Kematch and Steve Sinclair on 23 April 2000 in Winnipeg, Manitoba. The young Aboriginal family has a history of violence. Her family has substantial involvement with CFS. She was taken into foster care shortly after birth but was subsequently returned to her parents.

In 2001, Sinclair and Kematch have separated. The father Steve Sinclair has custody of Phoenix. In April 2004, Samantha Kematch took Phoenix. The mother had a new partner Karl Wesley McKay who has a long history of domestic violence.

On 11 June 2005, Phoenix suffered a deadly beating on the concrete basement floor of her family's home. A terrified stepbrother, whose identity is concealed by authorities, witnessed the assault.

Her death was not known to the authorities until her stepbrother did not blow the whistle until 6 March 2006. Samantha Kematch and her new partner Karl Wesley McKay were convicted of first-degree murder and are sentenced to life in prison with no parole for at least 25 years in December 2008.

Key events surrounding this case are summarized below:

The following events merit further discussion.

-

On 25 March 2011, Manitoba's Attorney General Andrew Swan decided to conduct an inquiry to examine the circumstances surrounding the death of Phoenix Sinclair under the Honourable Ted Hughes. The Manitoba Government Employees’ Union files a motion to suspend the inquiry on 6 February 2012, which was denied by the Court of Appeal on 16 February 2012.

All front line child protection workers are government employee union members. Their union acted against the inquiry to protect the workers who may have neglected and failed their duties. Although the union's action is to protect its members, it is clearly against public interest and natural justice. We are disturbed to see that the union did not take a more respectable position to better serve society and, above all, justice to the deceased.

- In July 2012, Hughes denies a motion to conceal the identities of social workers. This implies that someone has filed a motion to conceal the identities of social workers involved. Child protection workers are protected and privileged in many ways. Their identities are very seldom made public in cases where there are serious mistakes, public malfeasance, negligence, abuse of authority and tort. These god-like creatures have immense power backed by the deep pocket of taxpayers. Allowing them to conceal their identities adds difficulty to restore accountability.

Absurdities of CPS: a state monopoly

State sponsored child removal (or child protection as government would like its citizens to believe) is a government monopoly, which functions under the rules of command economy. It is under the strong influence, if not the direct control, of a cartel of bureaucrats and service providers whose job security, livelihood and main source of income derived from child removal. In Canada, child protection agency could be a provincial ministry (or department in some provinces) or a designated "non-profitThe term non-profit society could be misleading. The society itself may not be pursuing profit. But their directors and employees may. Directors and managers of many non-profit societies draw a high salary and receive good remuneration." society (such as the children's aid society in Ontario). They have different names suggesting the nature of their business is to protect child and family welfare. Despite their difference in legal structure and name, all child protection agencies are funded by tax dollars. Service providers in the industry do not achieve monopoly because of a competitive edge, an advance technology or a lack of viable substitute. By law, they are the sole service provider. Competition is prohibited. If any party other than delegated agents remove children, kidnapping is committed. Be mindful that once a child is removed, child protection agency becomes the sole guardian. Biological parents will be charged of kidnapping if they repossess their removed children. Apprehension of the Toronto couple Hung-Kwan Yuen and Anna Zhang in Richmond, B.C. on 25 October 2009 is just one of the many examples. Even unauthorized contact with removed children will have serious consequences (such as termination of supervised visitation, escalation of custody application). This does not mean that removed children are always safe in government's care.

Tragic deaths of young children caused by their parents or foster parents always draw intense public attention. The murder of 19-month-old Sherry Charlie in 2002 and the murder of the three young Schoenborn children (Kaitlynne, 10, Max, 8, and Cordon, 5) in Merritt, B.C. on April 6, 2008 are examples of the foregoing. Ironically, the child protection industry hits a jackpot when young children were killed by their parents or in foster homes. Government often responds by hiring a retired judge (the Hon. Ted Hughes O.C., Q.C. appears to be a popular choice) to conduct an inquiry and puts more money in child protection. The Phoenix Sinclair inquiry’s budget hiked from $4.7 million to $6.1 million in February 2013 and finally cost $14 million. Taxpayers are always an indirect victim. Although the child protection industry fails to fulfill its duty of protecting children, no service provider is held accountable. The identity of child protection workers in charge of the case is seldom made public. The industry suffers little damage when atrocities occur and ends up getting more funding and power.

Nothing is new under the sun. Like its counterpart Ministry of Children and Family Development in British Columbia after the death of Sherry Charlie in 2002, CFS emerged as a winner when its budget hiked at the expense of another young life. The child protection industry operates in the following unique ways that you will not find in any market economy:

- Because of the absolute power to remove children granted by child protection statute, service providers may define child abuse and have control of demand of their services. Child protection workers will exercise their child removal authority to ensure job security and to use up ministerial budget. Empirical data supporting the foregoing can be found in "Our Comment on When Talk Trumped Service" and will not be repeated here.

- State-sponsored child protection is a monopolized business. Service providers define the quality of their services. Objective performance measures such as the number of children died in care, low high school graduation rate of foster children, high percentage of crime involvement and welfare-recipient rate of foster care graduates seldom have an impact in refuting the self-proclaimed success in the child protection industry. Self-praising is the norm. For example, Alberta's foster parent association representative Katherine Jones alleged that their foster care system is the best in Canada in a fire fighting press conference in November 2013 after the media uncovered substantial number of unreported death in foster care, some died only after a few days in care.

-

Critical opinions and dissatisfaction of clients (parents commonly called by CPS service providers) are often ignored or suppressed with no consequence in the child protection business. Complaints often yield little results. Complainant with children under the provincial protection age limit run the risk of attracting retaliation. Fear, secrecy, ignorance and blind faith in government are their keys to success. The following are some cases of CPS retaliation after parents went public to air the corruption:

- the Bayne's case (2007 to 2011 British Columbia)

- Jessica Laboy case (2006 Florida)

- cases identified by WLKY 32 Investigates in Kentucky

- Child protection budget often increases after service providers fail their duty to protect. Insufficient training, case work overload, lack of resources are often cited as reasons of failure in subsequent inquiry. Recommendations always require more funding. Incidentally, the child protection industry benefits financially when it fails to do its job. The common sense management principle of rewarding success and reprimanding failure does not apply in this unique state and special interests joint monopoly.

In view of the above absurdities, restoring accountability is impossible. Corruption and racketeering are inevitable.

Child protection statistics in Manitoba

"Mapping out Manitoba's CFS system" by Mary Agnes Welch (21 December 2008) provides the statistics below:

|

Number of Children in care

Ethnicity of Removed Children as of 31 March 2008

|

Number of Social workers (more commonly referred as child protection workers in our site) Number of front-line workers hired since the murder of the 5-year old Phoenix Sinclair by her parents on 11 June 2005 - 99 Total: 697 front-line social workers Government Funding 242,893,800: provincial budget for child welfare in 2007/08. $89,851,600: provincial budget for child welfare in 1997/98. $48 million: Increase since Phoenix's death ($42 million in funding to agencies plus six million for foster families) |

Since the tragic death of Phoenix Sinclair, statistics above suggest the following:

- A 170% increase in provincial child welfare budget from 1997/98 to 2007/08;

- Like in the rest of Canada, Aboriginals remain the most prominent target in the child protection industry.

- Most child protection agencies keep statistics on the ethnic background of removed children and classify as Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal. The main reason of such categorization is for the purpose of claiming federal subsidies. Note that the federal government subsidizes the removal of Aboriginal children on a per head basis. Removal of Aboriginal children amounts to transfer payment to provide local more employment, business opportunities and, above all, more tax revenue.

|

|

|

|

Young children are often used to raise funds and to garner public support. At times, they are used to serve a political purpose. Residential school is an example of the foregoing when government used cultural assimilation to destroy the First Nation as a sovereign power that may threaten the legitimacy of the white man regime. Politicians like kissing babies to portray that they are family-oriented, approachable, trustworthy, likable, empathetic and popular. Elected officials from different political orientations are mostly pro child removal for political and economic reasons. Of course, they will never admit this and would like the public to believe that child removal decision is not made lightly and children are removed for their safety. You will hear this script on TV when a children minister is interviewed by reporter after an atrocity occurs in foster home.

Generally speaking, attempts to reduce a child protection budget or to restrict the absolute power of service providers are met with resistance at the political level for the following reasons:

- the risk of perceived apathy towards child welfare;

- the appearance of failure to protect vulnerable children;

- the risk of retaliation when the financial interest of the child protection industry is jeopardized;

- reduction of federal subsidy if fewer Aboriginal children are removed.

The notion of wrongful child removals and abuse of power is never addressed. Politicians turn a blind eye to these problems and consider that they do not exist. Decision makers do not appear to realize that some atrocities involving death of young children are unpreventable. An error does not become truth by reason of multiplied propagation, nor does the truth become error because nobody will see it. In many circumstances, more tax dollars allocated to child protection has little bearing in mitigating child safety risk. State funding certainly provides financial and job security incentive for service providers to remove more children. Under the pretext of child protection, social workers have absolute statutory power and job security incentive to do so with little repercussion. No one could hold them accountable. They act as business brokers to disburse funds in the child protection budget. Service providers in the industry all flock up to aggrandize. This opens government to corruption and racketeering. Errors do not cease to be errors simply because they are ratified into law. It is safe to contend that more children will be removed and more foster children will die in care if more tax dollars are put into the child protection industry.

References

- Grieving family demands answers by Kevin Rollason and Larry Kusch, Winnipeg Free Press, 17 April 2014

- Family pushes province for more info in infant’s death by Tamara Forlanski, Global News, 17 April 2014

- Winnipeg family seeks answers in baby’s death in CFS care by Eric Szeto, Global News, 15 April 2014

- Inquiry into the Circumstances Surrounding the Death of Phoenix Sinclair by The Hon. Ted Hughes O.C., Q.C., LL.D. (Hon), Commissioner, 31 January 2014

- Manitoba sorry for failing to protect Phoenix Sinclair CBC News, 31 January 2014

- Failing Our Children by Margo Goodhand (12 June 2009)

- Mapping out Manitoba's CFS system by Mary Agnes Welch (21 December 2008)

- BC Children in Care: Improving Data and Outcomes Reporting by Ian McKinnon, BC Children and Youth Review (April 2006)